More local than usual - Lisa's discoveries on Instagram during the lockdown: 'I passed two social distancing lines on my walk this afternoon: one at the fishmongers, the other at the bookstore. And people wonder why I live in Copenhagen.'

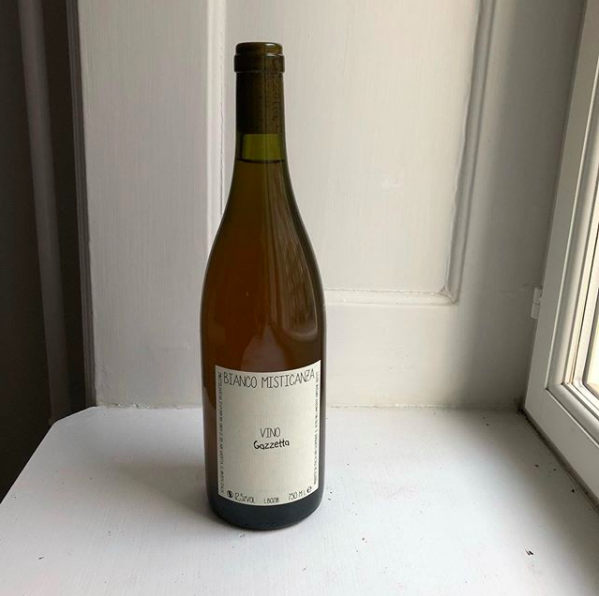

‘Hereby decree that all late afternoon walks shall culminate in bottles of orange wine.’ @lisaabend

The cemetery Vestre Kirkegård - one of Lisa's finds during long quarantine walks:

Home cooking delights: 'Some beautiful eggs from Lille Bakery'

Lisa Abend,

Copenhagen,

May 3rd, 2020

Portrait by Camilla Stephan

Restaurants, at least good ones, offer a space to escape. For some of us they are our second home. In the past months these places were taken from us.

In an attempt to find answers of what the future of gastronomy could look like after Corona I sat down with Lisa Abend, one of the most renowned journalists and international voices in the world of food. We had met the summer before, in 2019. With the overshadowing impact of Covid-19 it didn’t feel right to publish the conversation we had back then at this point in time. Instead, Lisa offered to share her thoughts and experiences of the past weeks in Copenhagen and her idea of what restaurants can look like once they reopen.

How did it feel to live in one of Europe’s most culinary exciting cities when all of its restaurants were closed?

It made me realise once more how lucky I am to be living here. First, because the government’s response was quick and effective. But also because although the situation is rough we have seen an unprecedented creativity. Restaurants came up with incredible takeout and delivery models which I have taken great advantage of. Just yesterday I had a Southeast Asian Fish Curry from Iluka. Beau Clugston, the owner, just showed up at my door. It is literally him and his partner who are doing everything from cooking and communication to delivering. The same goes for Lisa Lov from Tiger Mom. She offered take out right from the beginning of the lockdown. Her laab of braised pork belly with lettuce and ramson leaves is so fantastic. People were and are still in the position of making the best out of their situation here. In other places, like the US for instance, things are definitely worse.

The Danish government was one of the first to shut down businesses on March 13th. What was the initial reaction among chefs?

Even before the shutdown restaurants had already begun to get a lot of cancellations. Some restaurants fired people right off the bat, others tried to hold on to them. It went so far that some restaurants announced their closure like Kadeau, although they have now shared the good news that they will be reopening again. But it seemed to be a big fight. From the US we hear more tragic stories of icons shutting down like Gotham Bar & Grill. In the UK the situation is similar, I just read a terrible piece in the Guardian about the rise in homelessness among cooks and restaurant workers. People are losing their jobs overnight all over the world.

The response we have seen across the board derives from a deep desire to help.

What have you learned about restaurants in these past weeks that you didn’t know before?

To be honest how thin those profit margins really are. This is a known factor but although the government reacted fast – they first offered to pay 75% of the salary for the first three months if they kept their staff on the books – chefs still weren’t able to survive on that. Restaurants absolutely have no reserves whatsoever, it is kind of shocking. Eventually the government got a lot of input and raised the amount to 90%, plus they agreed to pay one hundred percent of all fixed costs. The government was very responsive from the beginning, and that increase also happened within a week.

It seems that creativity thrives within limitations. Almost overnight the gastronomy world created remarkable new business models. Is that because hospitality businesses typically work under pressure and adapt to last minute changes?

Yes, but I think there is a bit more to it. The response we have seen across the board derives from a deep desire to help. That has been really moving. It’s a reminder of why anybody goes into this business. To become a chef or a server you want to take care of people. That’s why you open a restaurant, you want to make people feel good and happy. What we see now is how deeply ingrained that desire is in the industry.

What story has stuck with you the most?

Especially in countries where there isn’t much support from the government like in the UK or US we have seen an extraordinary effort to take care of our own within the restaurant industry. Whether it is the Restaurant Workers Relief Program from the LEE Initiative which offers help to all the laid off restaurant workers or more on the global scale, what chef José Andrés is doing, is incredible. How somebody can go from his own little world of running fine dining restaurants to a global relief in such large scale is just mind-boggling to me. José Andrés was there right from the beginning, when that first cruise ship was quarantined at the dock in Yokohama in Japan to feed the healthcare workers and crew. By now his initiative has turned restaurants all over the US, Spain and Puerto Rico into community kitchens. He’s really become this incredible figure at the top of global relief. That to me is an amazing transformation.

After the crisis people are not going to want that restaurant as a stage and food as a performance but a restaurant as community.

How long can restaurants survive as community kitchens?

As long as the unemployment numbers are going up we will see a lot of them. But the question will be at some point where is that funding going to come from? I haven’t seen any answers to that yet. For a long time restaurants will have to face the question: How can we be creative in a way that will allow us to stay in business until a time when people are traveling again or even until they want to go out again. It’s not clear to me that, even if all of the travel restrictions are lifted tomorrow, people are going to want to get on planes or sit in restaurants. I don’t think it’s clear to anyone.

It seems Sweden is the exception, in that all of its restaurants have stayed open. You’ve talked to Swedish chefs and restaurant owners. Do you think that would have been the better approach?

I’m not an epidemiologist, so I don’t have any special insight into what the appropriate course of action is for any country in the face of this pandemic. But I will repeat something that Niklas Ekstedt, the chef-owner of Ekstedt in Stockholm, told me, and that I think is important to keep in mind: The Swedish government may not have legally forced social distancing, but it recommended that citizens practice it. And as Niklas said, Swedes are a people that when the government recommends something, they follow the recommendation.

In most parts of the world restaurants have reopened again, some of them in a different format. Noma, for example, started as a burger and wine bar before running something like ‘regular service’ again. What do you think will people want after staying at home for months?

I can only guess that if people are going to go out again they will have less money to do so. They are not going to want that restaurant as a stage, and food as a performance, but a restaurant as community. I tend to agree with René Redzepi who, in a piece I wrote, described that longing for a moment with friends gathering around a seafood platter. You just want that feeling of abundance and connection with the people who matter to you. And I think that’s what he is trying to do with his burger and wine bar. No reservations, nothing fancy, just a good burger and wine, and a beautiful setting where you can hang out with friends.

I would be absolutely thrilled right now to travel to Madrid and walk into Taberna Asturianus and order a plate of anchovies.

Is the crisis going to change how chefs cook?

I think so. Even before this crisis we started seeing first signs of people losing interest in the fine dining experience. They were getting tired of those long tasting menus, that feeling of not really having a choice. Of course, there’s always going to be a place for fine dining, and if the chef is good enough and truly has something to say, there’s a reason for tasting menus too. But in the last few years a tasting menu was adopted by restaurants that couldn’t really justify it. I suspect diners are also going to want food with big, satisfying flavours, not necessarily food that is provocative, intellectual or perfect. Certainly not food that needs a long introduction to be able to understand. Just warmth and conviviality, delicious food that is consoling and makes you happy.

The way you are describing fine dining suggests, that this world still values a labour-intensive dish over a simple, honest meal. Is it then our notion of perfection that has to change?

In a way yes. What still counts as perfect is this very intricate dish that probably 10 people have their hands on before it goes to the diner. But partly for the health reason: Do you really want that many people touching your food at this point in time? And also, as a consequence of this crisis, the kitchen staff as well as front of house are going to be smaller. Most restaurants are either not going to be able to afford the same number of staff or they are not going to have enough stagiaires flying in from all over the world to work for them. Which means they won’t necessarily have the hands to create the same kind of intricate dishes as they could before. But mostly, I wonder if there won’t also be a change in tastes, if maybe some of the more ostentatiously show-offy cooking will come to seem out of touch, as people’s values change. If they change, of course.

I see it as a chance for chefs to pay attention to the people around them.

Do you think people will travel again for a good meal though?

Eventually, I think they will again—I know I will if I can afford it. But what does that notion of a good meal mean? I think people are not going to care about perfection right now, honestly, I think we’re in the age of the good enough. As for me personally I would be absolutely thrilled right now to travel to Madrid and walk into Taberna Asturianos and order a plate of anchovies. That would really make my life.

It was once an indicator of great success for a restaurant to have guests that fly in for one night just to eat there. What will happen if international guests won’t fill the seats anymore?

I see it as a chance for chefs to pay attention to the people around them. It’s ironic: so many of those restaurants are built around a philosophy of the local, but their audiences are anything but. Especially at the fine dining level so much energy has gone into attracting international guests, that it has come at the expense of the people that are the closest, the people in your city, in your neighbourhood. It had to come to this crisis for them to actually get a booking. Danish friends here who aren’t part of the food world have often never even heard of some my favourite restaurants in the city. It reinforces the sense that we do exist in a bubble and restaurants at a certain level definitely turn outward rather than attracting their own neighbours. But the locals are the people who are going to get restaurants through this crisis, and figuring out a way to get and keep them engaged in your restaurant is an opportunity to show respect – not just for local ingredients, but for local culture too.

What can restaurants do now to appeal to their local clientele?

One of the easiest things that a restaurant can do right now is to do their social media posts in their native languages. Stop using English. I think for Danes, possibly for Germans as well, definitely for Spaniards, a social media account that is only in English conveys the message to locals that this restaurant is not for them. And with that may come other associations: the notion that it is impossible to get a reservation, or that the place is snooty and intimidating.

Will it be possible for the restaurant industry to recover from this crisis?

Restaurants have been around for hundreds of years, and I have no doubt they will still be there, and will thrive, on the other side. But the question is how many, and in what shape? The possibility of long-term damage is concerning, but so is the in-between period we are now entering. In Spain for example the government has now allowed restaurants to use outdoor seating but only up to 30%. That puts them into a position where they have to hire staff back, but they’re not going to be making enough to pay them. They are really in a bind. If governments are taking this gradual approach to reopening, which seems to be happening worldwide, this is going to be a huge problem for an industry that already has such low profit margins. How are they ever going to make it through the interim transitional period without any further governmental support?

The other change I’ve noticed in myself is a desire to use my work to make a difference.

In these uncertain times what kind of food has given you comfort?

Oh, carbs. So many carbs. I had to rein myself in because in the first couple of weeks I was just baking cakes pretty much every day. I was eating them all too, and a lot of pasta. I was talking to a friend the other day who is a food writer as well and it is funny, he asked me if I had noticed the increase in my meat consumption. And yeah, that is the other thing, carbs and meat. I think it is primal sustaining food I am craving right now.

Was there something you’re enjoying about spending more time at home?

Actually, what I’ve loved during this time, and what is pretty much my sole form of entertainment outside the home is going for really long walks. And it seems so obvious but because of the slow pace – usually I am on a bike – you notice things you never noticed before.

What have you discovered?

Right in the middle of the city is a building that used to be a sugar factory, and there is another which was the cigar factory. Other discoveries are all the old cemeteries which make up a lot of the green spaces in the city. On one of my walks I came across this special one, Vestre Kirkegård, which I later found out many people I know have a connection to. Discovering those parts of the city I didn’t know before has been my favourite part.

What is your biggest takeaway from this lockdown personally but also for the way you work?

Without a doubt, at a practical level, it’s had and will continue to have an impact. Restaurants are not the only industry being hit hard, of course. Media is too, and already a number of publications have either cut staff, like some Condé Nast magazines, or closed down all together. I am a freelance journalist, so I don’t have to worry about getting laid off, per se, but a lot of publications, including ones I write for regularly, are freezing their freelance budget. I also write a lot about travel and, well, that’s not happening any time soon. Like many journalists, I lost several assignments when the lockdowns started. I’ve been able to make up some of that work by writing about the crisis itself. I don’t know how long that will continue, however, and so financially, things feel precarious right now. But I’m hardly alone in that. The other change I’ve noticed in myself is a desire to use my work to make a difference, or to somehow help in a meaningful way. It sounds cheesy, I know, and I haven’t figured out how to do it. But I’m working on it.

Edited for length and clarity